A tool-strand post in an ongoing 2-strand series about Information Literacy

How can we foster a “slow search” approach that maximizes what we don’t know through discovery?

How can we take advantage of what we don’t know and use it more effectively in developing a search strategy?

How can the quest for quality also be built into the quest for information?

Fact or Fiction?

Kids like to search Google—and they think they are pretty good at it.

Kids like to search Google using questions instead of keywords, terms or concepts.

Kids expect to get acceptable answers to their questions—and tend to accept what they get.

When it comes to searching online, this skill is probably the one students feel the most confident about simply because they do it practically everyday for one reason or another. But in this case, familiarity and frequency do not equate to fluency.

Searching well is not just an essential 21st Century survival skill, but a must-have thrive skill. But how often is the skill of online searching directly addressed or discussed among the daily tasks engaged by students, unless it’s within the context of some kind of formal or assigned research endeavor?

The ubiquitous use of Google is both a boon and a bane to developing a student’s search skills, which include (to various degrees) the ability to evaluate, analyze, and synthesize what they do find, select, and decide to use in some way. The pluses are what we love about Googling—you can get thousands of results by simply typing in a few words; yet, even with its suggested search terms, knowledge graphs and related searches, it can be WYTIWYG situation: What you type is what you get. And since digital information is always growing and changing, it’s not exactly easy to find everything out there that could potentially connect to what you thought you wanted to find in the first place.

Another issue among students is their default habit and desire to do all of their searching by questions, instead of the concepts within their questions.

Well, if you think about how we think, it really is all about questions versus concepts, at least initially. We don’t think “cafeteria menu snack bar [today’s date]” but instead “Hey, I wonder if cheese sticks are in the snack bar lane today?”

The funny thing is that search engines like Google aren’t designed to provide results via question-style searches. We as educators know (in theory) that Google search works by using keywords and proximity (including your location) when you do a search to pull up what it thinks you are searching for…but it doesn’t operate by typing in a question; when you do get results via question searching, it’s because it found sites or pages containing that question. Students may or may not know this, but prefer to ignore it based on their experiences of getting results to their questions, probably because the question entered was one basic or common enough to have been asked and answered online already. Other features of Google’s search results, such as its knowledge graph and direct answers, aren’t always reliable; in some results, Google also may not credit where the source came from.

Combine this love of search-by-question with googling as a verb, and students can often feel they are done before they have even really gotten started.

And when it comes to evaluating the results before digging in, we have to face another fact—kids don’t really care about whether a source is reliable, credible, authoritative, or of a certain quality unless it’s required or expected explicitly by the teacher, or built into the rubric or assessment somehow.

Helping them move from question to query can be additionally challenging, especially when they aren’t sure what they don’t already know about a concept or topic. Kids often don’t know what they really need, what they are exactly looking for, especially if it is a true investigation beyond a basic fact-finding mission.

When we say, “think of related terms or keywords” or “use synonyms,” they often don’t know how to figure out what those are, or know how to mine them from their initial search results to further their “searchploration.” More often than not, students don’t know how to mine additional keywords, related terms and concepts as they search, mostly because they have become very satisficed with what they find right away, and are not necessarily driven by true inquiry when doing a search.

To them, a search is seen as a routine operation to get to the next phase (or to the end) rather than a crucial yet enjoyable phase of the entire inquiry experience. Unfortunately, Google may have also lulled students into thinking that it knows what they are thinking, and therefore is giving them exactly what they want and need via personalized search results, so why dig deeper by troubleshooting other possible combinations?

So how we can foster a “slow search” approach that maximizes what we don’t know through discovery?

How can we get kids to take advantage of what they don’t know and use it more effectively in developing a search strategy?

How can the quest for quality also be built into the quest for information?

One tool that can help with this is instaGrok.

instaGrok is both an online web-based tool and app (Apple & Android) that encourages students to “explore, understand, collect evidence” but not necessarily in a linear way, emphasizing the flexible and quirky essence of searching by moving back, forth, around and between what is found and what could be found.

How instaGrok Works

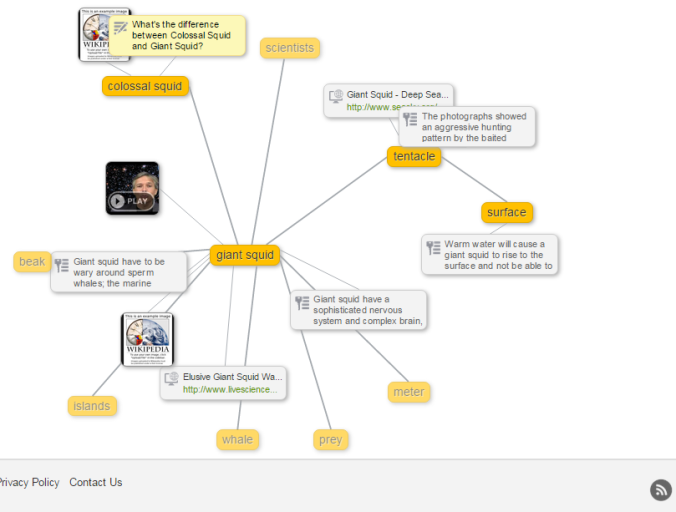

Free for students to use, instaGrok initially looks like a search engine, but displays results in the form of a “Grok”—an interactive concept map. By clicking on the initial concept nodes, a box will open for each displaying sources organized by key facts, websites, videos, images, related concepts, and a notes option for annotating that concept node. Each sou rce can be pinned to the overall map by clicking on a pin icon, saving it to the map. As you explore the Grok, you can make it grow and shape it by clicking and pinning any of the nodes and subnode words that appear.

rce can be pinned to the overall map by clicking on a pin icon, saving it to the map. As you explore the Grok, you can make it grow and shape it by clicking and pinning any of the nodes and subnode words that appear.

Once you click on any node’s source link, the page/site will open and you can read it right there inside the Grok; below the source page appears the note bubble option that allows you to pin the source, add a note about it, and even evaluate its credibility via a pop-up Credibility Form created by Easybib, which you can then submit to instaGrok.

Each Grok map also includes a toolbar featuring a Journal and Quizzes option. The Journal tab allows the searcher to begin drafting thoughts while the pinned items (including any user-created notes) appear to the right of the screen for reference. Also listed are all the source links as a bibliography which can be imported to Easybib and shared, exported or printed. The Quizzes feature includes basic multiple-choice questions from a source on the original Grok.

With a teacher account, you have the additional options to create classes and assignments, attach Groks to assignments, and view Grok histories.

What’s Cool About instaGrok

There are several things I really like about instaGrok.

Interactivity and Design via Concept Mapping

instaGrok’s interactivity and the way it groups and organizes media around a concept mimics and encourages visual thinking in the same way that we brainstorm and actually use brainstorming strategies like mindmapping via tools such as mindmeister, lucidchart, and mindomo.

Notable Node Content

What really impresses me with instaGrok is the quality of open web links in each node. If a student was to do a search for a term in Google, Wikipedia would most likely appear at the top of the results links. However, I did not find Wikipedia at all in any of the nodes I explored; rather, institutions and organizations like the Smithsonian, New World Encyclopedia, NPR, and TED.com were the sources for the key facts and Website link results in my “Giant Squid” Grok map. The one link to Wikipedia I did find was to a free-licensed image hosted on Wikipedia, but embedded in an entry from New World Encyclopedia. Most of the videos, although from similar .org and .edu entities, are hosted on YouTube, so the issue for students in viewing those would be determined by any campus or district filtering.

Making Connections

Another cool element is the option to make your own connections between concepts by adding a text bubble explaining how those are connected or related–in essence, adding their own meta-layer of meaning to the concept map.

Self-Differentiation via the Difficulty Slider

With the difficulty slider, users can control the level of results on each concept map. This builds in their own autonomy over differentiating their searching, since they control how challenging the content is that appears—and it’s flexible, so they can move up and down the scale as they explore.

Evaluating Sources On the Spot

Since each source pop-up window includes a link to a credibility form, students are constantly reminded about “quality” as a multi-layered criteria for choosing a source. Students also have the opportunity to improve instaGrok’s results for other users by submitting their own source evaluations, reinforcing the idea that even if it’s on a results list, it may not meet others’ standards as well as our own.

Notes Feature

As a searcher explores a node’s media content, she can add a note, which could be a quick jotting, annotation, or even a question. This notes tool could really be maximized as an in media res thinking tool for students, and as a way for the teacher to gauge their thinking as they explore; the notes also appear inside the pinned items on the Journal tab as reference for any writing they may do about what they have found.

Quizzes: Anticipation or Assessment Tool

The Quizzes tab includes basic questions related to the content from the Grok sources; this feature could be used as a way to check for comprehension, but also as an anticipation guide or scavenger search with students before delving into a concept together; these quizzes could also be used to generate more questions and potential searches.

instaGrok inside Edmodo

If you use Edmodo, you can also use instaGrok with students. Read here to find out more.

Ideas for Using instaGrok to Integrate Information Fluency

In the spectrum of Information Fluency, searching falls within the Ask and Acquire elements.

Ask—Includes asking questions, identifying keywords, brainstorming and lateral thinking, filtering out information “white noise.”

Acquire—Includes developing search skills, looking in more than one place, managing multiple sources, and comparing what you know with what you don’t—yet.

instaGrok can work on all of these facets simultaneously while making it fun and interactive for students, so they don’t realize what all they are actually doing besides just “searching.”

Chances are I will think of more ways to use instaGrok to integrate Information Fluency, probably as soon as I publish this post. For now, these are some ideas to get you started. As I think of other ideas, and if you think of any as well, please feel free to add them to this Google doc.

- Before introducing a new topic, unit or concept in your class, have students do a basic search in instaGrok, and share one type of media source they found. Go a step further and have them choose one of the potential pins and fill out the evaluation form and submit it; or use that same CC-friendly evaluation form and make your own as a Google form.

- Have students brainstorm a new concept or topic on their own using clustering or an online tool/app; then have them explore the same concept/topic in instaGrok, and compare their results, adding on to their original brainstorm or merging them by adding their own terms and connections to their instaGrok version.

- Journal: Idea 1

- Create an annotated bibliography using the bibliography inside the journal tab by explaining why each pinned source would be a useful one for a potential research-based project.

- Journal: Idea 2

- Instead of having them write a “research paper” about their search and sources, use the journal as a mini-I-search platform; after exploring their Grok, their homework could be to write a short reflection in the form of a KWL/KWHL or even a KWHLAQ.

- Genius Hour/20% Time/Passion Projects: When students are exploring a topic of interest, have them use the Journal as a way for you to formatively assess their progress on searching, connecting, and evaluating what they find to what they initially want to learn.

- Use the concepts as keywords to do a ‘Search-Off’ challenge comparing instaGrok to one of your school subscription databases, such as Gale, Ebsco or ABC-Clio. Mine the keywords, terms and concepts and build a giant concept map that charts/codes where the terms came from originally; then use that map to evaluate or reflect on the interplay and integration of a search strategy and search results in shaping the search process.

Pingback: Why we (and our students) should become Power Searchers | Curious Squid