How do we teach the art of asking questions?

A strategy-strand post in an ongoing 2-strand series about Information Literacy

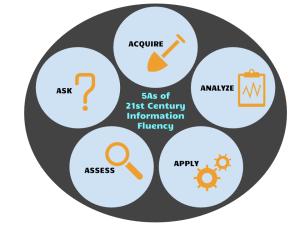

In the 5As of Information Fluency, it all begins with Ask—Asking a question about something you want to…discover, understand, learn, explore.

Warren Berger’s book A More Beautiful Question delves into the power of questioning and how it has led to groundbreaking innovations for creative thinkers, entrepreneurs and other leaders who work from an inquiry stance versus the status quo of seeking answers.

MindShift’s recent article lists learning how to ask questions as one of Five Critical Skills to Empower Students in the Digital Age (interestingly enough, three of these five are actually information literacy skills).

Yet despite the growing evidence and endorsement for questioning as a valid skill to cultivate among students, it’s still a task primarily owned and done by the teacher. As teachers, we often assume the role of questioner, versus shifting that role and responsibility onto the student.

So how can we more effectively teach students the art of asking questions?

Learning how to ask “good,” or “the right” or “beautiful” questions is sometimes seen as an art, and does actually require some finesse and practice.

Even as experienced teachers, it can be a bit challenging to hone our own questioning aptitude. In my own development as a questioner and a teacher of questioning, I have tried various strategies and exercises with students with mixed results.

When I first began teaching, I learned all about Essential Questions and how they can drive a curriculum centered on big ideas. Since then I’ve spent lots of time laboring over thinking up big, overarching essential questions to push exploration of a particular concept, theme, or unit of study.

However, through my own wrestling with developing these big questions, I realized that I was doing all the initial big thinking instead of the students. I also realized another innate issue with these types of questions—instead of sparking curiosity, they can potentially have the opposite effect of turning it off by coming across as too detached, lofty, or daunting to tackle, especially if the language seems inauthentic and canned.

As a librarian, I’ve looked around for ways to get the students to begin crafting their own questions, initially within the scope of doing their own research. One pre-research activity I used fairly successfully centered on guiding students through looking at a question’s “researchability” by classifying them as “inch,” “foot” or “yard” questions, based on a worksheet from Baltimore County Public Schools.

Then after attending a workshop by Jamie McKenzie and looking at both his book on questioning and his Questioning Toolkit (coincidentally also referred to in the MindShift article above), I revised the activity to include “convergent,” “divergent” and “evaluative” questions, along with a presentation to work through examples with students. Using a Question Frames Template adapted from one shared by Koechlin and Zwaan, students were then set loose to craft their own “researchable” questions.

Even though these activities helped students move from drafting basic fact-oriented questions to more “researchable” ones, it still felt as if I was placing too many parameters and pressure on them to generate bigger, deeper questions without taking into account the power a little question can have as the beginning impetus to investigation. Plus, the whole routine was still set within the context of the prescribed “research process” versus organic inquiry.

Then a few years ago while curating campus faculty resources to illustrate the oh-so-fun concept of “rigor,” I fortuitously stumbled across the QFT: Question Fo rmulation Technique highlighted in this Boston Globe article. Developed by the Right Question Institute, their site offers free educator resources on how to teach the QFT, including downloadable guides, presentations and tips for facilitating the technique with learners of any age. To learn even more, I highly recommend taking a good look at their book, Make Just One Change:Teach Students to Ask Their Own Questions.

rmulation Technique highlighted in this Boston Globe article. Developed by the Right Question Institute, their site offers free educator resources on how to teach the QFT, including downloadable guides, presentations and tips for facilitating the technique with learners of any age. To learn even more, I highly recommend taking a good look at their book, Make Just One Change:Teach Students to Ask Their Own Questions.

Warren Berger coincidentally spotlights the QFT in both his popular Edutopia post and on his own blog.

The beauty of the QFT is its seemingly simple process for teaching kids the inherently complex skill of questioning. What’s also great about this technique is how flexible and adaptable it can be for teachers to address both their content and skills simultaneously, while making the students do all–or at least most–of the work themselves. Through this process, they then create ownership of the questions and as a result, their own thinking.

Here’s a basic overview of the Question Formulation Technique:

1) Develop a Question Focus (QFocus)

Before generating questions, students need some kind of stimulus to ignite curiosity and prompt questioning. The QFocus can be a “topic, image, phrase or situation” that acts as the hub and the kernel for generating questions. One thing it cannot be is a question.

I would say from experience that this is the hardest part of the whole process—choosing or shaping a QFocus that is clear and focused enough so that it’s not too broad and intimidating, but also so that it’s not too limiting, inherently biased, or leading so that it hinders “new lines of thinking.”

For example, Climate Change as a QFocus is way too broad.

However, Climate Change and Our Food Supply or Climate Change’s future influence on our lives adds just enough focus to create that initial questioning spark.

2) Review the “4 Rules” of Producing Questions

This step strikes me as a pseudo-mashup of the rules of Monopoly with those of “Fight Club”:

- Ask as many questions as you can

- Do not stop to discuss, judge, or answer any questions

- Write down every question exactly as it is stated

- Change any statement into a question

3) Produce Questions

During this step, students must follow the rules for producing questions without fault.

4) Improve the Questions

Shape the question cloud by labeling them as either close-ended (yes/no/one-word answers) or open-ended questions (require an explanation), thinking of the advantages of asking both types of questions. The next part of this step is to then practice switching each type into the other in order to see how being flexible with their questions can lead them down paths to different discoveries and answers.

5) Prioritize the Questions

Working together, they agree on the top three Questions, based on the following criteria:

- the most interesting to them

- the most important to them

- ones that will best help them design the “task at hand” (what they will do with the questions)

- ones they want/need to answer first

6) Next Steps

This step basically addresses the question: What will you do with these questions? Since this technique can be done with any “task at hand,” it doesn’t have to just be for a “research project.”

Students can use these questions for…

- Beginning a new unit or topic

- Homework Assignments

- Independent Projects (Genius Hour, 20%Time)

- Group Projects (PBL, Guided Inquiry)

- Makerspace Projects

- Assessments

- Presentations/Reports

7) Reflecting on the QFT Process

This last step is crucial for providing you formative feedback on how students have begun internalizing this process; it also emphasizes the power and relevance of thinking about what they did, versus just doing the QFT as yet one more activity asked of them to perform.

In designing the reflection, you ask yourself two questions:

- What do you want to learn from students?

- What do you want students to think about?

How you want students to reflect is also flexible—individually, small group, large group, or a combination of all three.

The book gives some great examples of questions to ask, but the most basic are:

- What did you learn?

- What is the value of learning to ask your own questions?

- How can you use what you learned?

Information Fluency Take-Aways

The QFT is an accessible, adaptable method for developing the art of questioning in students, and works seamlessly as a way to weave the Ask element of Information Fluency into instruction.

In looking at all the steps more closely, Step 6 (Next Steps for Using the Questions) and Step 7 (Reflection on the QFT) tie in most strongly to certain facets of the Information Fluency spectrum.

By pondering their next steps, students must think about what they will actually do with their questions. In terms of finding information, they can then begin to dissect the questions and make a plan for their investigation by thinking about:

- what keywords in these questions will be the most useful for searching

- use the other keywords, related topics, tags, and subject terms to create additional questions

- develop a growing bank of questions—keep asking as they explore

When students reflect on the QFT process, they are also indirectly practicing the 5th A of Information Fluency: Assess. Assess in this sense means of both the product and the process, including reflecting on what they learned, how they’ve solved problems along the way, and how the experience has provided insights or opportunities for new learning.

This reflection step also conveniently supports the fifth critical skill mentioned in the MindShift article: the need for self-reflection in students.

So now the only question left to ask about the Question Formulation Technique is:

What are you waiting for?

And more thoughts, this time from Alfie Kohn… http://www.alfiekohn.org/article/questions

LikeLike

Pingback: @RightQuestion Digest 10/1/2015